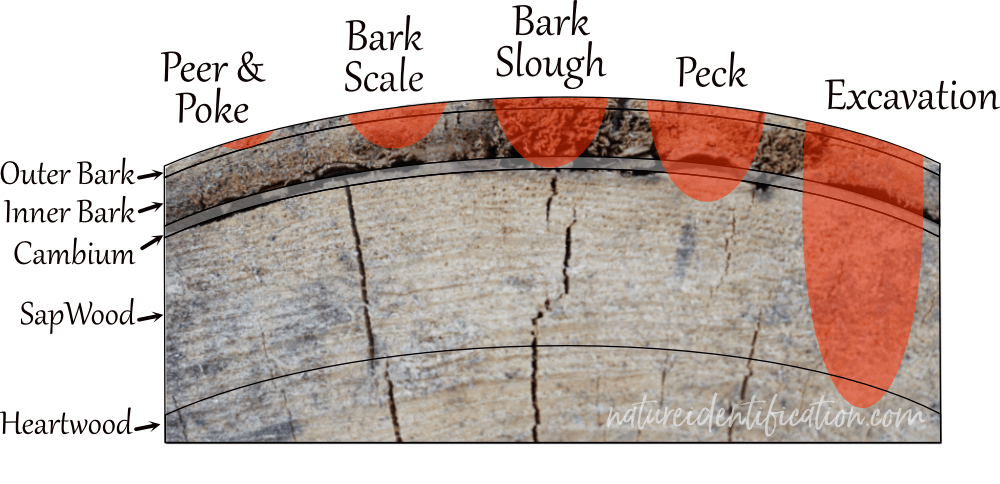

Many people associate woodpeckers with one or two distinctive holes found in trees, but woodpeckers can make many different types of holes and other marks/sign in wood. The holes and marks left by the woodpecker can tell you a lot about what the woodpecker was foraging for and can even give clues regarding what species made them!

1 – Peer & Poke (Bark Gleaning)

The peer and poke (bark gleaning) is a surface foraging technique where little to no damage is observable on the tree. The bird will move around the bark looking for (peering) and poking at various forage items. This is a very broad category of feeding and can include flicking off a small amount of outer bark to access a bug or simply pulling a bug off the bark’s surface. (6)

This is also the foraging technique with the largest diversity of forage items as there are many organisms found on/in the outer bark of a tree.

2 – Hunting Impact Marks

Woodpecker hunting marks are made when exploring. Most experts agree that woodpeckers have a keen sense of hearing that aids them in hunting for prey underneath the wood. The woodpecker taps the tree and listens for clues before committing to a deeper hole or a larger excavation. (7)

Much like a human searching for a stud behind a wall to hang a picture; the woodpecker will tap the wood to listen for any hollowness or irregularities that may indicate a beetle or ant gallery.

It is thought that by tapping at the tree – any bugs within the wood will get disturbed, causing those bugs to move. The noises created by the bugs allows the woodpecker to zero-in and grab its next meal. (8)

3 – Bark Scaling

Bark scaling is the removal of bark in flakes or scales in order to access insects within the bark. Bark scaling can be quite extensive, but the damage to the tree is usually superficial as the vital layers of the tree remain protected.

To find scaling behavior, search for any discoloration in the tree bark. The freshly scaled bark will be darker in color, and there should be no lichen or moss growing on the freshly exposed bark.

4 – Bark Sloughing

Woodpecker bark sloughing is the complete removal of the bark of the tree to access insect forage underneath the bark. In a healthy tree, the bark is tightly-glued onto the wood, so bark removal would be nearly impossible. As a result, bark sloughing is almost always associated with foraging on dead trees.

Removal of bark appears to be preparation for excavating in some woodpecker species. It could be that by removing the bark, the woodpecker optimizes its hearing to precisely target carpenter ants and wood-boring beetles living deep within the tree.

When a tree has recently died, the bark continues to adhere to the wood for some time – making it difficult to remove the bark from the wood. The removal of difficult-to-peel bark is called tight-bark sloughing. Tight-bark sloughing is associated with larger woodpeckers because of the strength and muscle mass this form of foraging requires.

Interestingly, tight-bark sloughing was one of the foraging behaviors biologists sought when trying to prove that the extinct-classified ivory-billed woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) still existed in Arkansas. (9) However, it was later recognized that the tight-bark sloughing they observed had been the work of pileated woodpeckers.

Bark sloughing is sometimes to be confused with natural bark fall-off and decay. Over time, a dead snag will lose all of its bark, so look for patches of bark removal within existing bark and test to see how loosely attached the bark is to the wood. If the bark can be removed without much effort – it’s likely the bark is falling off naturally.

5 – Sap Wells

Sap wells are unique woodpecker holes that are not targeted around a particular prey species. Woodpeckers make sap wells to draw out sugar-rich sap from a tree serving two functions: 1) The sap dripping from a tree is a desired food source for woodpeckers; and 2) the sap dripping from a tree is a desired food source for insects. Where there is sap, there is also the possibility of a yummy bug dinner!

Sap wells can be considered a type of passive trap as the woodpecker revisits these wells to feed on both sap and bugs attracted to the sap. The damage caused from sap wells can be extensive and can expose the tree to fungal and other microbial infections.

There are two types of sap wells: the xylem and the phloem. Their occurrence is dependent on the seasonal flow of energy and which tree layer is most active at the time. (10)

Xylem Wells

Xylem wells will be created in the early spring as the tree starts to send nutrients from the roots up towards the tree’s limbs and branches to start the season of tree growth. Holes created by the woodpecker to tap into the xylem wells have a typical size, are rounded in shape, and can be found wrapped around the entire trunk of the tree. In order to tap into the xylem, the woodpecker will damage through the cambium layer of the tree which can kill the tree as the holes accumulate over time. (11)

These holes could be confused with the work of wood-boring beetles. However, wood-boring beetle holes are expressed randomly on the wood and their tunnels are deep, whereas woodpecker holes in search of the xylem layer are arranged in an organized linear pattern and are shallow.

Woodpecker xylem holes can be seen across many different tree species including conifers and hardwood trees. Yellow-bellied sapsuckers (Sphyrapicus varius) especially love to drill these holes into apple trees.

Phloem Wells

Phloem wells occur after the tree has developed its leaves and nutrients begin to be sent down the tree through the phloem. Woodpecker holes created to tap into phloem wells will be found in late spring to summer and typically have a “blocky” shape/appearance rather than a rounded hole. These holes tend to be irregular in size and organized more vertically. To access the phloem, the woodpecker exposes the inner bark rather than extensively damaging it. (12)

Phloem holes are more frequently seen on sugar-rich trees such as birches and maples.

6 – Pecking

Pecking is common among all woodpecker species and is a very effective and precise means of foraging.

Woodpecker pecking is a direct strike towards a single target embedded in the bark or the outer layer of the sapwood. It may take several wacks of the woodpecker’s bill to get to the target, but it’s a direct route to its prey. The size and location of the strike often give clues regarding the size of the woodpecker.

Sometimes pecking, especially on birches, is accompanied by the peeling back of bark before digging into the wood. Birch bark may be hard to peck through, so peeling the bark back may save energy and frustration for the woodpecker.

7 – Excavations

Excavations are what many people think woodpeckers do all day long, and with larger woodpeckers in the winter season – that may be true!

Woodpecker excavations are labor-intensive holes that bore deep into the sapwood and heartwood. Excavations can be indicative of wide-spread infestations within the tree. These holes are usually meant to expose a colony of ants or beetles rather than a single bug associated with pecking holes.

Once a woodpecker has revealed a gallery, the woodpecker will use it’s long tongue to maneuver through the various tunnels to latch onto any ants or beetles. Their tongue snares the bug in two ways: with barbs on the tip of its tongue and with a sticky glue-like saliva. (13)

A woodpecker’s tongue tip is barbed for hooking prey. Different woodpeckers have varying numbers of barbs and appear differently, but they all have the same purpose – to catch prey. (14)

Woodpeckers also have a large submaxillary salivary gland which coats their tongue with glue-like mucus. As the tongue enters an ant tunnel – any ants or other invertebrates that it brushes up against will attach to their sticky mucus covered tongue. Basically, the tongue acts as a glue trap! (15)

After a woodpecker is finished feeding, the ecological value of a woodpecker hole only begins. Other birds, tree squirrels, flying squirrels, mice, and even raccoons are all willing adopters of woodpecker excavations as their new home. In many cases, various species depend on woodpecker holes for shelter as they don’t have the ability to carve through wood on their own. (16)

8 – Anvil Sites

Anvil sites are surfaces or crevices in which a woodpecker wedges a hard-to-open food item in order to secure it while the woodpecker cracks it open and feeds. In this way, the woodpecker is using the crevice as a sort of vise or clamp. A popular anvil location is within a crevice found in tree bark. Once a woodpecker has found an anvil site it likes, it often visits repeatedly, so look for multiple anvils on the same tree.

For example, in Europe, the great spotted woodpeckers will open tens, maybe hundreds of pine cones at the same anvil tree. Eventually these cones will fall to be seen at the base of a tree.

In the United States, anvil producing birds include nuthatches and red-cockaded woodpeckers (17)

9 – Cache Sites and Granaries

A woodpecker food cache is a place where a woodpecker has stored food in either larders (a food pantry) or scattered (singular food items) in order to sustain themselves for a period of time when food becomes more scarce.

Woodpeckers like the red-headed woodpecker (Melanerpes erythrocephalus) and acorn woodpecker (Melanerpes formicivorus) larder-hoard acorns in the fall and early winter in order to prepare for a hard land lengthy winter. (18, 19). In contrast, red-bellied woodpeckers (Melanerpes carolinus) will scatter-hoard items about 2 – 2.5 inches into crevices throughout the year. (20)

Most woodpecker caches are in tree cavities high-up off the ground; however, the acorn woodpecker makes unique caches that are much more conspicuous. The acorn woodpecker will carve an individual hole into a tree that will serve as a storage spot for a single acorn. When many acorn holes are carved into the same tree, this is called a granary. (21)

10 – Nesting Holes

Woodpecker nesting holes come in all sizes.

Foraging Techniques Can Tell You Why Woodpeckers Make Holes!

Quite a bit can be learned by simply examining how deep the woodpecker holes/sign go into the wood . For example, a deep excavation in the heartwood is likely created by a larger woodpecker going after ants or wood-boring beetles, whereas a bird “peering” and “poking” (often called “bark gleaning”) is likely foraging for any number of bugs and vegetation on the outside of the bark.

The below table and chart make some rough generalizations about foraging behavior, potential forage, and bird species. These are not meant to be absolute rules, but rather should function as a guideline to help understand the relationships among the different foraging techniques.

| FORAGING STYLE | TREE ALIVE/DEAD? | DEPTH INTO TREE | FORAGE | POTENTIAL BIRDS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer & Poke (Glean) | Both | Outer Bark | Flying insects, ants, various beetles, bug eggs, lichens, moss | Nuthatches, chickadees, brown creepers, warblers, titmice, small woodpeckers, medium woodpeckers, large woodpeckers |

| Bark Scaling | Both | Inner Bark | Various of beetles, bug eggs | Nuthatches, all sizes of woodpeckers |

| Bark Sloughing | Dead | Cambium | Bark and wood-boring beetle adults, larvae and eggs, ants, and other various bugs nested underneath the dead bark | Medium (when the bark is loose) and large woodpeckers |

| Sap Wells | Alive | Cambium | A variety of bugs that come to feed on the sap | Sapsuckers and ladder-backed woodpeckers (North America), middle-spotted and three-toed woodpeckers (Europe) |

| Pecking | Both | Sapwood | Wood-boring beetle adults, larvae and eggs | All sizes of woodpeckers |

| Excavations | Both | Heartwood | Wood-boring beetle adults, larvae and eggs, carpenter ant adults, larvae, and eggs | Small woodpeckers (in winter), medium-sized woodpeckers, and large woodpeckers |

Bug forage of many life stages (eggs, larvae, adults) can be found across all layers of the tree. Eggs and larvae are high in protein and fat, thus making them a popular food source for woodpeckers. Moth eggs are often found on the outside of the bark – often requiring only gleaning. Spider eggs are frequently discovered in the cambium layer of a dead tree, and may be revealed through bark sloughing. Carpenter ant eggs and larvae are usually deeply embedded into the heartwood of the tree in convenient masses, thereby offering a great reward for an excavator.

Various species of bark beetles can be discovered throughout the bark layers. The depth of the beetle in the bark, the type of tree, and the appearance of the beetle’s gallery can provide hints of the beetle species that the woodpecker was hunting.

Seasonal Changes in Woodpecker Behavior

Another factor to consider when observing woodpecker sign is seasonality. The season in which you find a recent woodpecker hole can potentially narrow down the species of woodpecker that made a particular hole.

For example, small-sized woodpeckers like the downy woodpecker (Picoides pubescens) are likely to only make excavations in the winter as other sources of forage become more scarce during this season. In the warmer months, forage options are more plentiful as more insects are available outside of the wood. Excavations are a challenge for the downy woodpecker with their small bill – so this is not their preferred foraging strategy. Downy woodpeckers are more suited for pecking and gleaning. (1)

Larger woodpeckers like the pileated woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus), pronounced both pie-lee-ay-tid and pil-lee-ay-tid, are likely to be found excavating at any time of the year because their body is more suited for the hard work of digging deep holes than are other woodpeckers. Pileateds have a much bigger bill, more muscle-mass around the neck, and can anatomically withstand greater impact from the constant pounding against the hard wood. (2)

Habitat Preferences of Woodpecker Species

There are also the habitat preferences among the various woodpecker species. Larger woodpeckers like the pileated woodpecker prefer foraging on the trunks and larger branches of trees. They also stay closer to the ground. The average diameter of a foraged stem by the pileated woodpecker is greater than 10 inches and their preferred height off the ground is about 18 feet. (3)

In contrast, downy and hairy (Picoides villosus) woodpeckers both prefer branches in the diameter range of 4 to 6 inches and they prefer to be higher up in the tree – about 23 to 43 feet high. (4)

Forest type and the tree species in which the hole was found are also factors to consider. Some woodpeckers prefer certain trees and forests compositions over others. (5)